The availability of public funding for some public services and programs is decreasing. If users and administrators of public services want to convey the value of those services to taxpayers, then it is important that they are able to articulate that value in a way that is useful, understandable, and backed by data. Franz (2011) encourages University Extension Services to get beyond conveying numbers of people who participate in a program to documenting the difference their participation has made for society. Articulating this difference, this public value, requires more than simply counting people and programs; it requires solid evidence and a clear message.

Embedded in the concept of public entities or public services, e.g., public libraries, Headstart programs, low income housing, Master Gardener programs, etc., is that they are of value or benefit to the public or community as a whole, as well as individual recipients of the service. Also embedded in the concept of public entities or public services is their increasing complexity. Silka and Rumery (2013) illustrate this complexity as they discuss the need for public libraries in the future. After reviewing recent trends and changes in libraries, they ask “in the face of increased emphasis on return on investment, what strategies can libraries use to measure returns on something as complex and multifaceted as the impact of libraries? As communities struggle to decide how to allocate their limited resources, can community-friendly decision tools be developed to help with the process?”

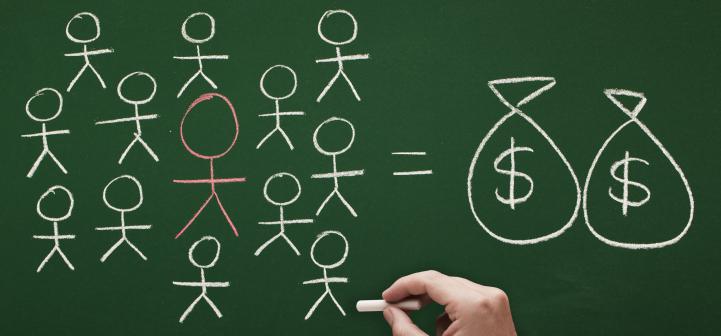

Silka and Rumery were wondering, in a nutshell, how to explain – or describe – the value of libraries to the public, especially to those who never walk through the library’s door. When we talk about the value of a public service, it can be divided into two parts –the private value of the service and the public value of the same service.

The private value of any public service is defined as the value accruing directly to the participants of the service (Kalambokidis, 2004). For example, people who visit libraries may borrow books or digital media for personal relaxation, attend pre-school story times or “read to a dog” programs to become more comfortable with and learn to love reading, or learn how to apply for a job and write a resume to become employed. Each library program has different benefits for participants; therefore, the private value differs for different library patrons.

Public value is defined as the value of a public service to individuals who do not use the service, but who benefit indirectly as others use the service (Kalambokidis, 2004). Early readers who become more comfortable and confident readers as a result of “read to the dog” programs tend to be more successful in school (a private value). They will, also, generally require fewer remedial education resources (a public value to all taxpayers).

Likewise, under- or unemployed citizens who learn how to research job openings and write resumes and become comfortable using online job applications are more apt to secure employment (a private value). They will, also, generally, have greater spending power to contribute to the local economy and need less public assistance (public value). Kalamabokidis (2004) and Moore (1995) propose that when a service is recognized as having significant public value, even citizens who do not directly benefit from the service will endorse its public funding.

Kalambokidis asserts that the importance of perceived value becomes critical when a service (e.g., a library) is not recognized as having significant public value, because citizens then believe the service should have the same status as a private good in which case that service should be sold in the private market for a price – hence the abundance of articles about the relevancy of public libraries. The question for administrators of any public service then becomes, “What evidence do we have that this program is valued by the public?” When this question can be answered and understood by the program’s administrators, then it can be explained in understandable terms to the community as a whole – not just the niche group who receives the service.

However, for “public value statements” to have public value themselves, they need to be true. Hence, solid research is needed to back up each component of the logic model in a public value statement to be sure it is more than just wishful thinking.

So let’s quickly look at a logic model for the Read to a Dog program that was referenced above and ask questions about the ‘evidence’ to support what is being claimed.

- Is there research that supports the claim that “children having a difficult time that read to a dog and learn to love reading and improve their reading skills?”

- Yes, and it is fairly solid. The person relating the ‘story’ doesn’t need to go into the details of this research, but they need to know it exists and be able to provide it to the few who want to access it. For example, when library advocates claim their “read to a dog” program helps kids, they need evidence this statement is true such as the information provided by Intermountain Therapy Animals.

- Is there research that supports what the logic model ‘says’ about the the private benefits (in the illustration it is the orange/red box)?

- Yes, but this is not as directly linked to “Read To A Dog” but to early childhood education. Of equal importance here is the consideration that lots of programs sound great in theory but do not really deliver in important ways that create value for non-patrons. If this program was just fun for children to read to dogs, but did not improve their reading skills or willingness to read, it would have no benefit to those who don’t use this service.

- Is there research that supports what the model says are the public benefits (in the illustration this is the yellow box)?

- International research on the public value or indirect benefits of libraries or public library services is still in its infancy and there are relatively few solid studies on these. Here, logic is more likely to be needed until the empirical research catches up.

Coupling this type of evidence with a clearly articulated message (the Public Value Statement) can be the difference between a vote to terminate funding for a public program or a vote in favor of continuing ongoing financial support for a valued public service or public program.

Credit:

Franz. N. K., (2011). Advancing the public value movement: Sustaining Extension during tough times. Journal of Extension [On-line], 49(2) Article 2COM2. Available at: http://www.joe.org/joe/2011april/comm2.php

Intermountain Theory Animals. “Research and Results” website

Kalambokidis, L. (2004). Identifying the Public Value in Extension Programs. Journal of Extension [On line], 42(2) Article 2FEA1.Available at: http://www.joe.org/joe/2004april/a1.php

Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Silka, L., &Rumery, J. (2013). Are libraries necessary? Are libraries obsolete? Maine Policy Review 22(1), 10-17 Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol22/iss1/4/